Founded in 2005, Geez magazine is a publication about social justice, art, and activism. It proudly claims that it’s “for the over-churched, out-churched, un-churched and maybe even the un-churchable.”

Started by Aiden Enns in Winnipeg, the magazine has been run since 2018 by a staff based in Detroit, who embrace the fierce independence of the magazine’s mission and are deeply devoted to living out its ideals in both its pages and business operations.

In this conversation, editor Lydia Wylie-Kellermann and associate editor Kateri Boucher discuss their approach and goals for continuing the publication known for dreaming big, providing a home for both play and prayer, and supporting contemplation and social action on the fringes.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Brittany Wilmes, Faith and Money Network: Talk about your upbringings and how you found your way to the magazine.

Lydia Wylie-Kellermann: I was raised in the Detroit Catholic Worker community, so I grew up with a bunch of families that all lived on the same block in southwest Detroit who were committed to gardening, resistance, and civil disobedience. It was a real gift in terms of forming my own ideas around faith, and that for me, it could never be separated from justice. For a lot of us growing up, our parents were trying to do war tax resistance, which meant living below the poverty line. Parents were working part-time, but they were also around, spending time with kids.

In high school, I realized, oh, this is my work, too. I started writing for Geez right after college, and I wrote a piece for young people on why peacemaking matters and what that commitment looks like. I later became the Catholic Worker section editor, and in late 2018, Aiden Enns, who had founded Geez 15 years earlier in Winnipeg, reached out asking if I’d be interested in taking over the magazine.

Kateri Boucher: I grew up with parents and wider families raised Catholic, and I started my own journey going to a radical Catholic church, Spiritus Christi, in upstate New York. I went to college and felt more interested in exploring different forms of spirituality, moving away from Christianity. I studied sociology in college, and got a grant to do research on urban farms. To do that work, I spent a month in Detroit on the recommendation of my dad, who had been working with Lydia and her dad [writer and activist Bill Wylie-Kellermann], and I lived on the block where Lydia had grown up. It changed my life. It had to do with both faith and money. Seeing the way Christianity was lived out, through this new experience — I didn’t know you could live this way. That was a big moment in my life.

I went back to school, and all the time, I was thinking, I just want to go back to Detroit. I moved here for good in the fall of 2018, without a real plan, and it was a couple weeks after I moved when Lydia handed me the Gender Flex issue of Geez and said, “I might be about to become the editor of this magazine. Would you join me?” I haven’t left Detroit, haven’t left Geez.

Wilmes: How would you introduce a new potential reader to the magazine?

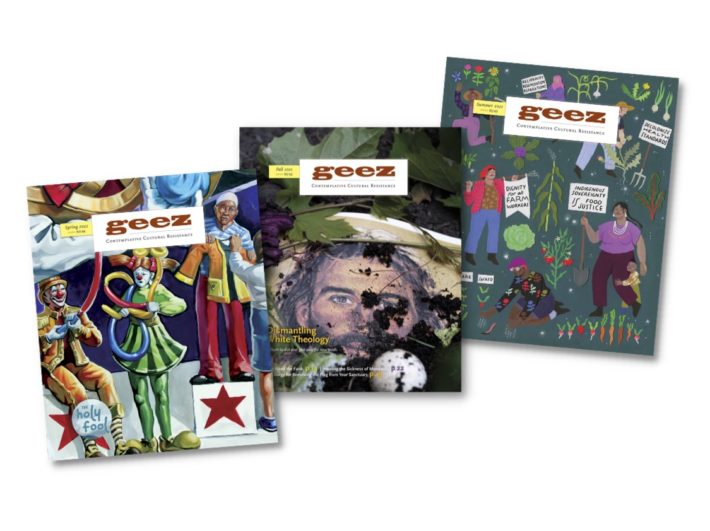

Wylie-Kellermann: Geez is an ad-free, quarterly print magazine at the intersection of art, activism, and spirit. Each one of those pieces feels really important. The commitment to ad-free is part of our commitment around faith and money. This is a print-or-die project. We’re not interested in ways for folks to be more connected on screens. You can leave it on a coffee table, read on a bus, or take it to the woods. One of the taglines that came from the Winnipeg team that I really appreciate is that Geez is “a prophetic voice to the institutional church, and a pastoral voice for those who are laboring on the frontlines of social change.”

We often talk about being on the fringes. The magazine is for those of us who believe in liberation and justice and community. The original tagline was “holy mischief in the age of fast faith,” and now it’s “contemplative cultural resistance.” We try to hang onto both.

Boucher: The magazine is very community-based. We receive contributions largely from our readership. Anyone from the community can pitch a story or an artwork, and the issue itself ends up being a community document. It’s not that Geez is giving a resource to the community, but rather creating a space within the community to talk to itself and be in conversation with others who are in it.

Wilmes: The magazine is run as a nonprofit and is proudly ad-free. Talk about the business model behind the magazine and how it’s tied to your editorial mission.

Wylie-Kellermann: I feel like I’m always saying that Geez is a very bad business plan. But part of our mission and vision is to be anti-capitalist. We’re talking about that constantly – both what that looks like in our pages and what it means to run the magazine as a business. Ad-free is a piece of that — we’re not trying to sell anything in the pages. We’re looking for this to be a contemplative experiment. That means that we’re almost 100% supported by our readers and community, through subscriptions and donors.

We also know that print is a bad business plan. That’s not where folks are thinking right now in terms of what’s possible or sustainable. And I think we’re always thinking about the ways — part of our work is storytelling, and we know that budgets tell stories and that they articulate what we care about and how we’re operating in the world. We want to look at that together as a staff and a community and be transparent about that story. We’ve moved to putting that on the website, to say, here’s the story in numbers.

Boucher: What allowed us to get this off the ground when it moved to Detroit was that all the staff, but particularly Lydia, were willing to take on lower wages to get this going. A phrase we used at one point was that this project, especially at the beginning, was very subsidized by community, and the ways we were sharing resources outside of this work. I’d babysit their kids one night a week, and they’d make me dinner that night. We were already in a resource-sharing community with each other, and that really allowed us to keep our budget smaller.

We’re very grateful that we are able to support our staff with fair, solid, hourly wages and other benefits that we’re continuing to grow.

Wylie-Kellermann: Our first fundraising letter said, send us vegetables! Whatever it is, we’ll happily trade that for a subscription. We’re always wondering, how can we figure out how to exchange this resource without money?

We’ve had to lean into a sense of mystery and trust when we’re trying things to see what happens. That’s a real skill that we have to cultivate in the midst of empire, when we’re told that everything is scarcity.

When we moved from Canada to the U.S., that was very hard for our Canadian audience. There’s a lot of pride in our being founded there, and so we kept the subscription price $39 for both audiences, whether folks are paying in U.S. or Canadian dollars. We call that our empire tax.

A year ago, we put out our Jubilee economics issue, and one of the decisions that we made at the same time was to move to a sliding scale subscription model. When the magazine came to us, subscriptions were $39/year. We needed to rethink that number, and we decided we wanted to make it accessible to everyone, so we created a sliding scale from $20-150.

You say where you are and what your needs are, and we laid out our own budget beside it so that folks could understand it. In the first quarter, we made $5,000 more than we would have made in subscriptions previously. Somehow, our budget comes out right in the end. We can’t quite explain it, but we trust it and we’ll continue to do that.

Wilmes: Staffers at Geez are also activists, caregivers, and entrepreneurs. How does the staff manage to integrate the work of creating the magazine with other areas of focus?

Boucher: It’s been really important since day one for all of us. At the time, it made sense for each of us to start working part-time, but it has been such a gift, with every person having their feet in multiple spaces. Having work that we do outside of Geez, both paid and unpaid labor and the communities that we’re a part of, we see Geez as benefiting from that, and our communities benefit from the work we’re doing at Geez. For me, my other part-time job is working at this church where Geez has an office, so my commute between offices is just one floor. We’ve each grown through the places where we have feet in other spaces, and it continues to nourish us and our work with Geez.

Wylie-Kellermann: We talk about Geez coming out of community and giving back to the community, and that feels really crucial. We’re not working 60-hour-weeks under a deadline, not engaged with our bodies and the local places where we live, but instead we’re living and breathing and working with the community.

Boucher: In terms of the business model, I think that as a contractor, most people working in this general scenario are experiencing a lot more uncertainty and instability. What allows us to be working in this way is that we do trust that if something terrible happened or we needed to take some time off, we would be able to figure that out as a community and an organization. We’re willing to take some small risk in that. We don’t have full benefits, but we do have the trust.

Wilmes: Lydia, you took a recent leap across the country to start another position. How did you make that decision, and how does it affect the organization?

Wylie-Kellermann: I didn’t see it coming, and it created a lot of grief to pull up very deep roots in Detroit. Kateri has talked about both the pain and hardness and also the incredible imagination and community that comes out of that place. Detroit is such a model for us in terms of living out questions: How do we create community? How do we grow our own food? How do we create mutual aid?

It was a big deal to shift away from that, but the job of director at Kirkridge Retreat and Study Center came open, and it’s a place where I grew up, coming as a child when my parents were involved with anti-war organizing. My sister and I were running around the land and falling in love with these mountains. It’s a landscape that is on my heart.

There’s a hunger for what this moment is on the clock of the world, as Grace Lee Boggs asks. I think there’s a hunger for gathering in community, and that things feel really scary. There’s so much grief and so much rage. There’s a hunger for being on the earth and being with one another and finding space to grieve and to dream, and this is a place to be able to do that. I’m really excited about the ways that I think that work will merge with Geez.

When Covid first hit, we wondered a lot what that would mean for Geez. So many folks had lost jobs, and one of the things that goes first when you don’t have money are subscriptions. But it was the opposite — our subscriptions grew dramatically. We could just feel this hunger and loneliness, a hunger to gather in community with folks who are asking the same questions, a space to tell stories. I’m excited to think about the ways that this place could facilitate gatherings for the Geez community.

Wilmes: How do you bring practical matters like economics and personal giving into the magazine’s tradition of storytelling?

Wylie-Kellermann: I think there are ways that it runs through everything. There are specific issues where we’re talking about money, like pieces on wealth redistribution. But it’s also in everything. This next issue is about craft as resistance — craft as soul-tending and ancestor remembrance, but also about survival and simplicity. There are so many ways that economics feed into that.

Boucher: What I appreciate is there’s an acknowledgment of our own individual lives, balanced with big-picture conversations about the structures that we’re living in. I can’t really imagine an issue that wouldn’t have the word capitalism in it. Part of what we try to do as an editorial team is to bring real vulnerability and honesty around one’s social location, hoping that others can use this space to say things that they might not feel normally free to say. We try to create a space and an environment where that’s always part of the ethos even if it’s not being specifically named.

Wylie-Kellermann: We have a clear editorial commitment that it’s OK to make mistakes, and we’re going to learn from it and say we’re sorry. We have a lot more freedom to experiment and try things and continually ask, how do we be more human?

Wilmes: Kateri, you’ve phrased one goal of the magazine as featuring both the reverent and the irreverent in every issue. How does this show up in the magazine?

Boucher: It’s an aspiration to live into. We’re always pondering how those things are balanced. I can speak very specifically about a couple of recent issues, which have had one piece where the contributors were turning the topic on its head. For example, in our Global Solidarity issue, we were receiving pieces on the reverent side, more serious reckonings with missionary work. And then we received a pitch about the necessary weirdness of “sillydarity” work. It played a really important role in the issue. The opening line is, “We’re gonna fart this place up!”

Same with our White Theology issue — we had a piece submitted called “We Need the Funk” about not taking ourselves too seriously. Our editorial team tends toward the reverent on the spectrum of things. Our community and contributors help us bring in the irreverence. It’s a challenge to weave them together gracefully.

Wilmes: You’ve featured Ched Myers and other familiar names to the Faith and Money Network community. How have you introduced your readers to Sabbath economics?

Wylie-Kellermann: When we think about being a pitch-driven magazine, it happens in the pieces that we publish. There is a lot of work to do — we probably need to stretch more and have some serious conversations about wealth, and how much shame there is when activists find themselves with wealth or inheritance unexpectedly. There are big questions there around giving. I’ve been really grateful for Susan Taylor and the Just Money folks, too, for helping me reckon with those questions. As activists, we’ve gotten used to talking about simplicity when it comes to our money, and there’s more we could do on the flip side.

Boucher: The Jubilee issue was so fun, because Jubilee also represents rest and return. It’s so imbued in every issue of Geez. The concept of Sabbath jubilee – we hope that that spirit is part of every one of our issues.

Wilmes: How do you build community beyond the pages of the magazine?

Wylie-Kellermann: Our readers are super engaged. When Covid hit, we started a pen pal program. People built some really great relationships. We’ve hosted some digital courses related to an issue theme. We’ve also started joint community conversations between Geez and Kirkridge. We get so many ideas, but we can’t turn them all into issues. So once a month for an hour, we open up a conversation, like: What does it mean to identify with Christianity in this moment in time? We’re always wanting to hold that line of wanting to be print and local-based but also create a broader community, even online.

Boucher: One other word about the community aspect: We do so much place-based work and grounding and rooting, but we are totally spread around Turtle Island [Ed: Turtle Island is a name for North America used by Indigenous peoples and activists.] and around the world. People have said they think of Geez as their community just from reading the magazine. It’s such a unique space at the intersection of activism and spirituality and Christianity. There aren’t that many people in the country who hold this combination of relationships to capitalism, community and spirit. People let us know that they do think of it as a place that they’re able to go or a spirit that they’re able to sink into.

Wylie-Kellermann: One of the projects that we did this summer was about grounding in local community. We asked ourselves, what does it look like to do marketing at this moment? We don’t want to buy ads as much as we don’t want to run them in our pages.

So we exercised our creativity. We hired 17 people from around Turtle Island and said, we’ll give you $500 this summer to spend 10 hours building community. Some folks had Pie and Poetry events, some had a Holy Fool party where everyone had to dress in costume, one person held a collaging party with old issues of the magazine, and another took issues to the farmer’s market. It was really exciting to see how we could reimagine marketing.

Wilmes: What are you looking forward to in future issues?

Wylie-Kellermann: Our winter issue is on Crafting as Resistance. We’ll have a Bread and Wine issue for the spring, our Kids issue in the summer, and a Saints issue in the fall.

Time and efficiency have a lot to do with capitalism, too. We’re planning themes out more than a year in advance — we are not a news magazine. News can’t be what we offer, and so there’s also some mystery in that. We did an issue about civil disobedience that landed right before George Floyd was murdered, or an issue about trees that landed right before covid hit, and people were hungry to be outside. We’re not going to pay for the most efficient software or processes. We’re moving slow, and we trust the slowness.

Wilmes: Is there anything else you’d like to say about the magazine that we haven’t discussed yet?

Wylie-Kellermann: One of the things that we thought about last fall was that we’ve applied to a decent amount of grants and we don’t get them. We’re too political for religious grants and too religious for political grants. Last fall, we came up with the idea of mini-grants, and we went to our community and said, here’s what we need to fund. We need, for example, $2,000 to have a staff and board retreat. We put these ideas out to our community and said, be our grant funders. We did that for the first time last year and it was hugely successful to see our community say yes.

Boucher: I’d like to give gratitude to the Winnipeg team and to Aiden Enns for holding down and passing along the values to the magazine, but also releasing attachment to the ways that we do things. That was a really beautiful business model.

Interview by Brittany Wilmes | November 2, 2022

Brittany Wilmes is a freelance writer, editor, and project manager based in Portland, Oregon.