Lydia Kelsey Bucklin isn’t afraid to bring an expansive sense of creativity and mission to her work in the Episcopal Diocese of Northern Michigan. As Canon to the Ordinary for Discipleship & Vitality, she lives and works in a beautiful, remote region of the United States where the traditional model of one priest per congregation isn’t self-sustaining, and hasn’t been for decades.

In this interview, she spoke with us about how her diocese has been a pioneer in rethinking ecclesiology, how local leaders welcome visitors and train others on the collaborative ministry model, and what it looks like when a church community and a small-town brewery share the same roof.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Brittany Wilmes, Faith and Money Network: Tell me about your diocese and how you found your way to the work you do today.

Lydia Kelsey Bucklin, Episcopal Diocese of Northern Michigan: I was raised here in the Upper Peninsula, and it’s a really interesting place to live and work and have our being in that it’s pretty isolated and remote. It’s a peninsula that’s separated from the rest of Michigan. It’s 30% of the landmass of Michigan, but only 3% of the population. So it’s roughly a third of the size, but tiny in terms of the people because it’s all forest and it’s surrounded by the Great Lakes.

Our winters are very rough and very long. We probably have nine months of solid snow. So people who live here are hardy and faithful and deeply committed to the land, to community, and are kind of used to being the underdogs. I would say that people here are scrappy and resilient.

I feel like we’re the canary in the coal mine in some ways, because we were starting to see 30 years ago what the rest of the church is experiencing now, which is that smaller communities of faith with the model of one priest per congregation just wasn’t sustainable.

Samuel J. Wiley, who served as bishop in Northern Michigan in the early 70s, wrote what became a historical text on rural community ministry. It’s called The Celebration of Smallness (PDF link).

Everyone told him he was crazy for coming to a place like northern Michigan, that it was career suicide, that nothing good would come out of this place. In response, he very much leaned into celebrating smallness and the beauty of small communities — and then theologically related that to early Christian living.

We live based on a sufficiency model. People sometimes talk about scarcity versus abundance, and I would throw in the word sufficiency. Having enough means it’s enough.

Often in the church, as in our society, we want more than enough. We bury our treasures because we’re so afraid of running out. And so we have to practice living with enough for what God’s calling us to do.

That requires a lot of faithfulness, especially when numbers are small, when populations are aging, when extractive industries have changed the landscape and depleted the local economy.

Often in the church, as in our society, we want more than enough. We bury our treasures because we’re so afraid of running out. And so we have to practice living with enough for what God’s calling us to do.

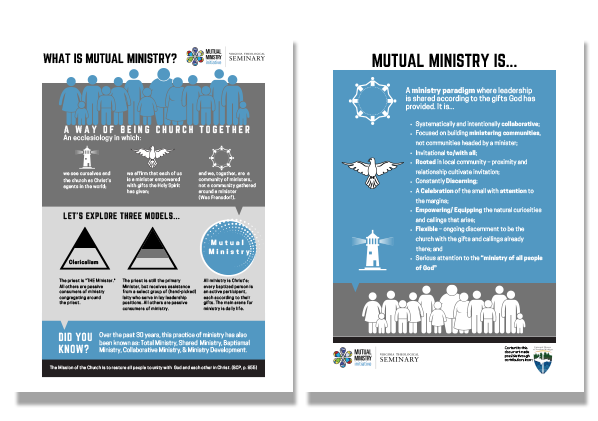

The next bishop of northern Michigan was named Tom Ray, who led the diocese here when I was a child. I was raised within this model which we call mutual ministry, where rather than our churches having a minister at the middle who we all rely on, we’re ministering communities with a circular model of leadership where all of our gifts are necessary and needed, and we all play different roles in that.

We really work to honor one another and give each other opportunities to use our gifts, whether we’re ordained, whether we’re not ordained, whether we’re paid, whether we’re not paid.

We’re all called to hear what God’s calling us to do. And often that work is in our daily life and in the midst of community. So it’s okay if when we gather on Sunday morning there are eight of us, because the impact that the eight of us have on the circles around us is exponentially larger. And as long as we’re using our ministry in daily life, we’re all using our gifts to work towards God’s dream, which is peace and healing and justice work.

For me as an ordained clergy person who happens to have a seminary degree and to be paid, it’s a much better way of doing ministry. It’s much more freeing to be able to focus on the things that I have real gifts and passions for and let go of those things that I don’t have gifts and passions for because as great as I think I am, I can’t do all the things nor should I, and in overfunctioning as we often do as clergy, we’re taking away opportunities for the people in our communities.

One of the things Tom Ray used to say that I love is that when access to the sacraments is tied to our operating budget and however much we can pay for those sacraments, that’s a social justice issue.

I think that’s really powerful because it speaks to not just rural isolated areas, but also inner cities, multicultural communities, refugee communities, places that have historically been under resourced or cut off from any of our major denominations who also deserve access to things like communion, baptism and the rest of the sacraments.

Wilmes: How has the diocese responded as others have come to you with interest in replicating this model of leadership?

Bucklin: We’ve been having Visitors’ Weekends for decades, and we hold two a year. People usually come from the U.S. and Canada, but also all over the world to be immersed in baptismal shared ministry and to hear from people in our local settings.

Those have been amazing, not just for sharing with people, but for the communities themselves to share their stories. For a small town and group of people who are faithfully engaged in ministry to have people come from somewhere else to want to hear how they’re doing it and to be inspired by them is a shot in the arm.

There have also been some organic networks. One was called Living Stones Partnership, which was a group of dioceses or seminaries or judicatories if they were outside the Episcopal Church, who would pay a membership fee on an organizational level and then send people to a yearly conference that acted as a think tank and place to share case studies. We dissolved that partnership a couple of years ago, because it often hinged on leadership and whether the active bishop supported the effort.

We now have a brand-new group called the Living Waters Cooperative. In this arrangement, each member is the owner. We have an active Facebook group, we’ve done two retreats, and we host an open space conversation once a month on Zoom that anyone is welcome to join. These are where we talk about collaborative ministry, decision-making and how to do formation in a collaborative way, to give access to all of our information.

We’re trying to build up a grassroots network and to have it more racially and ethnically diverse — it tended to be more white and rural in terms of who was participating in the past. It’s been cool to see it grow from the ground up.

Wilmes: What can it look like to adapt this model to different places and roles?

Bucklin: Every place would need to look at this way of being church in a really unique way to design something that works for them. I think in the past, people took the model that we used up here and it didn’t work. We’re small enough that we can all gather in one room and make decisions collaboratively, and when you’re in a much larger geographic region, it’s a little trickier to get everyone on the same page.

The other group we often hear from is people who are entering ministry and wondering how they can lead in a way that welcomes this collaboration.

They’re asking, how do I as a clergy person go into a community and not overfunction or presume to know best, but also still provide enough structure and care and live into my role as a priest?

There are people who think that a shared ministry model is just for those who can’t afford better. The shift that we need is to say, no, it’s simply that moving away from a consumerist, transactional model of ministry is just who we’re called to be as church.

Peter Block’s work around building community has been really important to us here to understand how all of that matters as we approach living this way on both the macro and individual levels.

Wilmes: Your title is Canon to the Ordinary for Discipleship and Vitality. How does that reflect the work you do that’s unique to your region?

Bucklin: The discipleship piece is about empowering and equipping folks to be disciples from all ages. If we are called as followers of Jesus and claim that through baptism or through association with community, then what does that mean in terms of living authentically into that?

I think in the past, as a church, that’s turned into kind of like a to-do list of all the tasky Sunday things that make a good churchgoer — serve on the vestry, be a reader, and so on.

Some of the call is reframing it into what it means to fully integrate discipleship into my life. So I ask myself, as a mother of two young children, where am I called into reconciliation? Maybe it’s with my son and one of his friends arguing on the trampoline in our backyard. I’m as called as a priest in that moment towards reconciling and sharing God’s love as I am on Sunday morning from the pulpit. We really encourage people to live into that.

And then the vitality piece is taking that balcony view of our communities of faith, helping communities reimagine what it means to be a church and how to use space.

Wilmes: What are some examples of how that vitality has been brought to life in new ways?

Bucklin: One unique example is happening now in a small mining town called Ishpeming, where the church group was struggling with an aging building. It was costing too much, with lots of maintenance expenses and not much money coming in.

They could have said, OK, we’re closing up shop, we have to figure out what to do with the building. But in this town, a church building is not a hot commodity in terms of developers wanting to buy them up. Once the mines shut down because they extracted all the local resources, they took everything and left. We have lots of empty storefronts in Ishpeming.

So we talked to members at Grace Church and asked them, what makes this community unique and different from the other local churches in this town of 6,000? What would it mean to be in partnership with the community and provide a space that is needed?

We tasked members with going out and having conversations with people in the community. It turned out that in the alleyway right behind the church building was this little brewery that operated in a rented space that wasn’t working great. The owner was a lifelong electrician who has a real passion for the community and he said, I’ve got this dream that this pub would be the community hub. It’s a new movement coming out of the UK where the pub becomes the center for community again, where there would be wakes at the pub and everybody would come and turn to each other and share their sorrows and celebrate life together but then also maybe get some counseling or job help at the pub.

His name is Jay Clancy. He said, I just have this dream of wanting this to be the gathering place for our community, not necessarily even around alcohol, but just around caring for one another in this place. I remember sitting with him and saying, “Wow, Jay, that sounds a lot like the church!”

Lydia helped found the Mutual Ministry initiative (MMi) at the Virginia Theological Seminary and now serves as a senior advisor. Learn more about how this initiative is training future Episcopal leaders on mutual ministry principles.

Want to learn more about Mutual Ministry? These downloadable PDFs from MMi explain this emerging ecclesiology.

He ended up purchasing the church for $100 and taking ownership of the building, which now is called the Hygge Center. The church community has been meeting there on Sunday mornings for worship. And the idea is that it’ll be remodeled with the pews taken out and turned into a gathering space that can be used for all kinds of events in the community.

Something similar has also happened in one of our churches in Calumet, which is up in copper country. A member of the ministry team was on the board for the local food pantry, and their rent had gone up. And they said, we would love to host the pantry here in our local church, but we don’t have ADA access. We were able to find some grant funding to finance the easement and do some retrofitting work on the outside.

And now the food pantry is going to be moving into the basement, and the church community has an idea to remove the pews and create a labyrinth space as a quiet place for people in a town that’s increasingly overtaxed by tourism demands.

It’s a historic landmark. It’s on park land. And so the church members said, what if we take out the pews and put in a labyrinth and provide this space of calm meditation and prayer, open to everyone? They’re asking bigger questions that reimagine what’s possible in these very small places.

From my perspective as a diocesan staff person who works to help support the communities, leaning into the invitations to partner in the community has been really important. They’re not all perfect solutions, but they’re ways of responding to however God’s calling us in the moment.

One of the other biggest growing movements of ministry in our diocese is called UP Wild. It’s a wild church movement that is now active in three areas, starting in the Marquette area where I am and then expanded to the Houghton area, which is copper country, and then down in Delta County, which is along Lake Michigan.

It costs nothing because people gather on the water or in the forest. They’re doing forest bathing. They’re doing meditation. They’re doing deep sharing. The theme of last month, when I offered the reflection, was “Can you remember who you were before the world told you who you should be?”

And so it’s people who, for the most part, were raised in the church but left because they were let down by the institution, but have found God and connection to the divine out in creation and are longing for community to connect with.

The questions we ask ourselves at the diocese are, is it a church? Not necessarily. Is it a worship community? Yeah. Do we need to ask people to convert to anything? Maybe not. But then how does that fit within a diocesan structure? Those are all the big questions we’re facing as things change.

But the Spirit is absolutely at work in our people and communities. And so part of that vitality piece is around the question of what it means to continually be transformed and to be open to that and to be able to adapt to it.

Bucklin on the beauty and challenges of growing the shared ministry model:

“There are people who think that a shared ministry model is just for those who can’t afford better. The shift that we need is to say, no, it’s simply that moving away from a consumerist, transactional model of ministry is just who we’re called to be as church.”

“Whether or not we grow financially or not is actually not our main goal. And in those ways, we often appear and talk about living in more of a Franciscan model, where if you’re rooted in poverty and sharing resources, you’re not worried about it as much.”

“Embracing mutual ministry, with a flat model of leadership where regional missioners all have the same salary, is something that people in other dioceses or judicatories are not often willing to do. When I worked in other dioceses, the bishop made twice as much as the next highest paid. That’s a different way of living. So when people say, we want to share ministry, we ask, are you willing to actually make these changes? And some people aren’t. And that’s okay. It’s not for everybody, but it’s a choice.”

“Our way of being is a threat to the empire. Because it shows that maybe all of that isn’t necessary — maybe all the elitism and all the pretentiousness isn’t what the church has to be. But that threatens a lot of who we have been and how people have gained power.”

“It’s a gift because it’s a shift away from fear.”

Interview by Brittany Wilmes | September 7, 2023

Brittany is a freelance writer, editor, and marketer based in Portland, Oregon. She has nearly 15 years of experience working with nonprofit organizations, helping them to grow communities that are grounded in integrity and to tell their stories with vision and creativity.