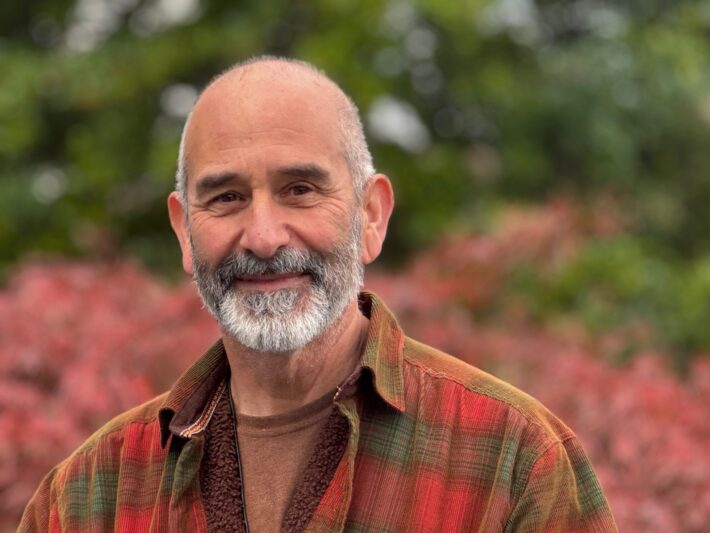

Sensei Joshin Byrnes is the founder and guiding teacher of the Bread Loaf Mountain Zen Community near Middlebury, Vermont. His background in Catholic social justice and his Zen Peacemaker practice of social action has led him to participate in Faith and Money Network programming, most recently attending the Fall 2023 Trip of Perspective to Central Appalachia.

In this interview, he explained how Zen Peacemaker tenets mirror the “inward/outward” work long embraced by the Church of the Saviour (and Faith and Money Network), why he takes groups of Zen practitioners to the streets to experience homelessness firsthand, and how his own grappling with matters of faith and money have brought a new perspective to his teaching.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Brittany Wilmes, Faith and Money Network: What’s your story? How did you find your way to the work that you do today?

Joshin Byrnes, Bread Loaf Mountain Zen Community: I’m a Zen Buddhist priest and teacher in a Japanese lineage, but here in the U.S., that Japanese lineage gave birth to another lineage called Zen Peacemakers. The Zen Peacemaker order focuses on working in the cracks of society. We say we practice with social action, and it’s a core practice for us to actually be engaging with some of the bigger challenges the world faces and some of the larger challenges that our communities face.

My own spiritual background is that I was raised Catholic. I actually was in the Dominican order for a number of years and went to theology school. I had taken vows and was studying for the Catholic priesthood, but eventually left the Dominican order. However while I was there, I was introduced to liberation theology and the social teachings of Jesus that I think inspired me and clarified some values that I carry.

Then I left Catholicism in many ways for a long time and worked in the AIDS epidemic for about 15 years at the intersection of public health and social marginalization. That was a specific time and place with a lot of human suffering. And given that I had left Catholicism behind, I was doing a lot of that work disconnected from any kind of structured contemplative practice and also any belief system. I was doing it really as a secular humanist, which was fine enough. But I did find that after 15 years, I was pretty depleted.

So I began to look to the East for mindfulness and meditation practices, embodied yoga and yogic practices. And eventually I found myself in the insight meditation path of Buddhism, which opened up for me into Zen Buddhism. As I got deeper into Zen practice, Zen Peacemaker practice brought together a lot of threads for me.

Wilmes: Tell me a bit more about the Zen Peacemaker tradition and Bread Loaf Mountain Zen Community.

Byrnes: Zen Peacemaker practice works in these more marginalized, intersectional cracks of society. It embraces all religious wisdom perspectives, including people who are not religious. It is organized around values, which we call ethical precepts, and how to practice them in real life, not just in our heads. Zen is practiced in a way that is pretty inclusive of a very wide range of people and social concerns, and that appealed to me.

Over the years as a Zen practitioner, I’ve engaged in a practice of periods of voluntary homelessness through a practice we call Street Retreats, where I go out on the streets and often bring other practitioners out on the streets to plunge into these environments and to confront a lot of our assumptions and misconceptions about these places, to develop a more intimate relationship with the sidewalk itself, the soup kitchens, the people who are out on the streets, to all of life, actually, on the streets. And then through being intimately connected with those people and spaces and places and issues, to allow a response to arise out of that.

A lot of the programming that we do at Bread Loaf Mountain is a response that arises out of our connections to places like the streets, and people that we had previously alienated from our awareness.

I found my way to Mike Little’s work because I’ve been interested in the intersection of Buddhist and Christian practice around some of these issues that challenge the world today. And what caught my attention was Faith and Money Network’s direct approach at looking at where our spiritual lives intersect with our money lives. Given my interests in poverty and homelessness and economic suffering, I was interested in exploring my own relationship to money and to explore it through this Christian framework as a way to look into some of the things that I’d put in the recesses of my own awareness and consciousness.

So I participated in Mike’s program.

Wilmes: That was the Money, Faith and You class?

Byrnes: Yeah. And through the experience of writing the Money Autobiography, of thinking about issues related to scarcity and abundance, of thinking through what the prophetic voice might be at this time, it opened a certain view or perspective for me.

It enriched my Zen practice, which was working in some of those same spaces and asking many of the same questions. I’ve been teaching a two-year training program called The Infinite Circle, which looks at the intersection of dharma, or Buddhist teachings, and Buddhist life and Buddhist practice and our relationship to money at the individual level, the community level, and the economic level. So, being part of Faith and Money Network has also enriched the way I approach this from a dharma perspective as well.

Wilmes: What is your experience in the Zen Peacemaker tradition of guidance or transparency around money?

Byrnes: In the last 50 years, I think dharma communities have done a lot of really good work on a number of issues like race in America or ecodharma concerns or death and dying.

But I feel like there’s a gap around looking deeply at our relationship with money, both at the personal level and also at the organizational level. What are the business models that dharma centers use and how aligned are those with a Buddhist teaching or perspective on our relationship with money?

The Buddhist view on money is a little different from a Gospel-based perspective on money. But I do think we have a lot to learn from people in Christianity who have been really looking at this question of what it means to operate out of a framework that says, blessed are the poor, and that sees intrinsic value in simplicity and poverty. I remember how as a Dominican, I took a vow of poverty — it’s elevated to that level. It means it’s a space of inquiry.

I feel like what we’re contributing at Bread Loaf Mountain Zen Community and some of our community projects is a place where we can sit with the question of what is it to live a dharma-inspired life in a money-driven world?

What I appreciated about the Money, Faith and You course was the degree of disclosure and transparency at the personal level, which from a Buddhist perspective, I would say, is a kind of way of taking responsibility for the suffering of the world. That’s an important Buddhist practice. You don’t see suffering as something you observe on the outside, but you recognize that you’re complicit in the systems of suffering that exist.

Mike’s work around transparency and disclosure held me accountable to my own relationship to money. The Money Autobiography did that, in going deep into where I picked up my beliefs and feelings and discomfort about money and what remains secret for me about my relationship to money.

And then the practice that they have at the Church of the Savior, which is to disclose publicly to the community how much money you have and how much money you will give to the congregation, was particularly moving for me.

So I sprung a surprise exercise on this cohort of people who were in my class called the Infinite Circle, where I said, well, today I’d like you to tell me how much money you have.

And of course most of the group was shocked, which simply revealed how much hiddenness there is in our relationship to money. What Mike’s developed is a helpful and skillful way to penetrate into the secret recesses of our relationship with money and therefore with economic systems.

Wilmes: Can you say more about your community programs? We’ve talked briefly about Street Retreat, but do you have other offerings?

Byrnes: So, there are two things that we practice, with two program types. The first is a plunge. Street Retreat is a plunge where we, with very little, simply show up in an unfamiliar setting. We don’t have any money or change of clothing with us. We have the clothes on our back, one dollar in our pocket, and maybe a blanket or a sleeping bag. That’s all we’ve got.

We show up in a city and we just find our way. Where to find food, where to go to the bathroom, where to get information about a safe place to sleep at night, how to find cardboard to sleep on. There, we’re just kind of dropping in.

Our main aim is to practice not knowing, which means simply letting go of our fixed ideas about these places and the people we encounter in them. If we think of these places only as horribly suffering places, we miss some of the other realities going on in these places, like where joy comes from, where hope arises, where generosity arises. We are trying to open our eyes a little wider to see all aspects of the situation.

For example, if we see these people only as a diagnosis, we never open up to the whole person. And so we’re letting go of fixed ideas about them and also fixed ideas about ourselves. We often think of ourselves, because of our privilege, as helpers. And if we only think of ourselves as helpers, then we’re never actually open to being helped. There’s something very powerful when you recognize that you’re being offered something by others, and that your job is to receive it.

By engaging in not knowing, we’re able to become the situation itself. You recognize that I am you and you are me in some really fundamental and basic way. And what we share is the truth of birth and death and life. No matter what kind of degree or background or good fortune or bad fortune or diagnosis you have, we are intimately entwined.

In the Street Retreats, it’s out of that intimate entwinement that actions arise. So that’s plunge. We don’t do any study or reading about the situation, we’re not talking to activists. It’s an embodied practice, and we’re holding everything equally without a lot of judgments or analysis. We’re just becoming it.

In bearing witness, the second structure, we use many of those same principles as in plunge, but we’ll go into a place for a number of days and we will have studied this situation.

So for example, I went to Auschwitz concentration camp and spent a week there and I studied the Holocaust from multiple perspectives. I studied the names of people who had been killed there. I also studied the names of people who were perpetrators there. And I went into places where people were victimized and where people also were perpetrators. And you begin to see everything there as suffering.

So you go into those settings and you’re actually studying, you’re exploring, you’re engaged in inquiry, with different aspects of the situation. Like, what is the Nazi perspective here? What is the Jewish perspective? What’s the perspective of a bystander who lived in the town? You’re taking in quite deliberately all those perspectives. When I do that, I realize that there is a little bit of perpetrator, victim, rescuer, and bystander in me, and my practice is to transform my own suffering into compassion, insight, and healing actions.

Part of why I went to Appalachia with Faith and Money Network is because we’re going to do one of these Bearing Witness retreats there in a year. It’s very similar to how Mike set up a Trip of Perspective.

Wilmes: What are some examples of what these core programs have evolved into?

Byrnes: Out of the Street Retreat practice, which I’ve been doing for 10 years, one of the things that’s come back to me often is the pandemic of loneliness that people experience. And out of that, I’ve felt the impulse to create spaces where people could get a little bit of relief from loneliness, but also begin to talk with people who are outside of this socially constructed bubble that we all exist in.

Part of the loneliness is that middle-class people rarely actually talk to lower-economic-class people. People who experience mental health challenges are operating in a system where they are forced into the identity of being a client all the time, which ignores all other parts of who they are. When are they ever able to be with people who have a different experience of money and mental health and not be viewed as a client or a person in need?

And what is it for someone who’s often thinking of themselves as a helper or a donor or a volunteer to let go of those identities and just be in neighborly relationship with someone who is really struggling economically or with mental health issues or substance use disorders?

So coming out of Street Retreats, we started with hosting a free cafe in one of our local towns that has a high rate of people living in poverty. We wanted to create a place where people could just mix over a meal and where it wasn’t like a soup kitchen line of food that reinforced the helped vs. helper mentality.

That then evolved through COVID into a food truck. We hosted pop-up food events that were really not about addressing hunger, but about addressing loneliness and alienation. We did that for two years and then that evolved into a project we call Gather, which is an open door community living room where everyone in the community is welcomed and to simply come and spend time with other people.

It’s not a social service organization, it’s not delivering client services, it’s simply a living room that’s owned by the community. A lot of people come there now: students at Middlebury College, attorneys or judges or social service workers or teachers, people who are living in low-income or subsidized housing, people who are receiving client services, those who are living in different encampments around town, to people who live in their cars and are moving through — that whole rich, supreme meal of people are showing up at Gather. And they’re spending time with each other. And we are forgetting for a little while who the helper is and who the helped are. And I think something rich is blossoming out of that.

This practice has allowed me to become more sensitive to some of the systemic dynamics that perpetuate economic suffering at the community, state, and national levels. So I then engage in different task forces, policy groups, and advisory committees to say, well, here’s a perspective, here’s what I’m hearing. And I also bring a spiritual dimension into it, which is: let’s not limit how we view people just by their material needs.

Let’s look at them as whole human beings who have joys and sorrows, who grieve, who have fallen in love, who have losses, who have a future, who have imaginations, who have aspirations and hopes.

This is an example of healing action — that we can bring a lived perspective to these discussions as a result of our practice of plunging into these environments and becoming intimate with people in them.

Wilmes: What was your experience on the Trip of Perspective to Central Appalachia?

Byrnes: The experience was, top to bottom, a really powerful and both heartwarming and heartbreaking experience. I wanted to be sensitive that we’re a bunch of people at the northernmost part of the Appalachian Mountains. At the top of the mountain range, we’re mostly white, well-educated, middle- and upper-middle-class progressive, elite people popping into an environment where we might not have been invited.

I really trusted Mike that it would be okay for us to come. And getting there, we were so graciously and warmly welcomed by the people he’s been working with over the last 12 years in southwest Virginia. They really helped us understand aspects of life there that have been so marked by a certain way of engaging with land, money, race, political ideology and religion.

For me, the most heartbreaking moment was when they took us up a mountain to look down on a mountain that had its top cut off in being mined. It’s just a shocking scar on the earth’s skin — an open wound.

And there we were, surrounded by all this natural beauty — the trees, the birds, the flowing water, the fresh air — it was all so healing. And then there’s this opening and you look down onto the mountain and you see this destruction. It would be very easy to become really judgmental about that.

But I felt that Mike and the diverse group of activists that he’s been working with there had a very compassionate view of what was going on. Yes, it is a deep cut into the skin of the earth. And yet at the local level, it has provided a kind of basic and necessary economic sustenance to people who live in that region. In a troubling way, it has been driven by the economic interests of people who do not live there and do not have to suffer the consequences of it. So, what a complicated environment. The earth is damaged and the people who work there benefit somewhat economically from that industry, but are also harmed by it.

There’s the physical injury and moral injury of it. Black lung is the obvious physical injury, and the moral injury is harder to put your finger on, but miners are in this relationship to the earth that is not characterized by union or by the truth of the interconnected nature of us and Earth.

And on top of that, there’s this awareness that the larger system is being driven by a global bottomless hunger for consumption, which of course we’re all a part of. I’m not separate from that. You know, I drove my car down there. I participate fully in an economy that depends on the mining of that coal.

And so there’s this aspect to it of, yeah, you could turn the coal barons into evil monsters, but that really isn’t taking responsibility for the situation.

Their lives and our lives are connected. And there’s no avoiding that truth. The conversations that Mike set up with the activists and the reflective processes we were engaged in helped us see our role in this whole complicated system.

And did so in a way that was compassionate, but also challenging, confrontative in a way. And in the context of the opportunity to come into real relationship and friendship with people who live in that region, who are so different culturally, politically, religiously than me who lives up here in Vermont in a Zen community. That turned into a multidimensional, really rich experience.

In Zen, we use these things called koans, like, what’s the sound of one hand clapping? They’re little statements or stories that are structured in a way that is meant to disrupt your linear or dualistic way of thinking.

For me, going [to Appalachia] was like a three-dimensional, embodied koan that challenged linear ways of thinking and added the dimension of relationship and embodiment to it.

Interview by Brittany Wilmes | November 7, 2023

Brittany is a freelance writer, editor, and marketer based in Portland, Oregon. She has nearly 15 years of experience working with nonprofit organizations, helping them to grow communities that are grounded in integrity and to tell their stories with vision and creativity.